This report and our

campaign are dedicated to all those individuals, communities and organisations bravely taking a stand to defend human rights, their land, and our

environment.

Last year, 196 people were murdered for doing this work.

We also acknowledge that the names of many defenders who were killed last year may be missing, and we may never know how many more gave their lives to protect our planet. We honour their work too.

Nonhle Mbuthuma successfully stopped destructive seismic testing for oil and gas off the Wild Coast of South Africa. Despite ongoing threats to her safety, she remains dedicated to defending her community and environment. Thom Pierce / Guardian

We will not be silenced. We will keep making history

Nonhle Mbuthuma, 2024 Goldman Prize Winner and founder of the Amadiba Crisis Committee

It was like a bomb had been dropped on us. We had just learned that the petrochemical giant Shell was looking for oil and gas off the coast of South Africa, close to where I live. Not that anyone had bothered to inform us – not our government, not Shell, not anyone else. We heard it in the news.

Little did it matter that our Constitution clearly states that we must be consulted. Like so many other land and environmental defenders around the world, we found our basic rights violated. Yet I count myself lucky because I am here to tell my story.

As this new report documents, 196 fellow defenders can’t tell their stories; they were brutally murdered in 2023.

This report shows that in every region of the world, people who speak out and call attention to the harm caused by extractive industries – like deforestation, pollution and land grabbing – face violence, discrimination and threats.

We are land and environmental defenders. And when we speak up many of us are attacked for doing so.

South Africa’s marine environments are stunning. Like many peoples and cultures worldwide, the Indigenous Peoples of the Eastern Cape find solace and leisure in our oceans.

But to us, they are more than sandy shores and turquoise waters. They are a vital food source and a lifeline for millions of people. They are home to many endemic marine species. They are sacred places, with deep cultural meaning that stretches back generations.

Shell’s seismic exploration rights were revoked and ruled unlawful by a South African court in September 2022, following a campaign by residents. Rogan Ward / Reuters

Imagine, then, how I felt when I learned that Shell was going to carry out months of seismic blasting – an activity as bad as it sounds – in biodiverse coastal waters near my home.

The blasting zone in Maputaland-Pondoland, Albany, would cover 6,000 square kilometres – two and a half times the size of Cape Town. Shell’s path to further oil and gas extraction would not only be catastrophic for marine life, but also for people and for our planet.

This is when I understood how invisible we were and just how little companies like Shell care about their impact on the climate, pollution, and biodiversity – collectively, the greatest human rights challenge of our generation.

The breach of these fundamental rights by governments and companies in pursuit of profit is not just minor collateral damage. Their actions have life-changing consequences for us all.

Like many communities facing environmentally destructive projects on their doorstep, we knew the only way forward was to build a movement across South Africa.

The breach of these fundamental rights by governments and companies in pursuit of profit is not just minor collateral damage. Their actions have life-changing consequences for us all

Nonhle Mbuthuma, 2024 Goldman Prize Winner and founder of the Amadiba Crisis Committee

Together, ordinary people – including families, activists, journalists, lawyers – worked to show our government that there is another, more equitable path to power the future. Our message resonated beyond our coastal towns, and our movement quickly swept across the world.

We were up against a multinational company and a government that had been supportive of its plans. Regardless, we took Shell and our government to court. And our perseverance and determination paid off.

In September 2022, the Eastern Cape Division of the High Court of South Africa revoked Shell’s exploration rights and ruled that conducting seismic surveys on the Wild Coast of South Africa was unlawful.

This was a landmark decision and a historic win for us. We felt vindicated. But our joy was short-lived. The judgement was quickly appealed, and we are waiting to learn the date of the next hearing.

Whenever it may be, we’re ready.

Nonhle Mbuthuma, a 2024 Goldman Prize Winner and founder of the Amadiba Crisis Committee, leads the amaMpondo community in South Africa. Thom Pierce / Guardian / Global Witness / UN Environment

Being an environmental defender does not come without personal sacrifice. Decades of working to protect our planet have taken a toll on me physically and emotionally. There is a hidden cost to our activism.

For years, I have faced death threats, brutality, criminalisation and harassment. Knowing my life is in danger every day is deeply taxing. And I know I am not alone.

Since Global Witness started reporting on killings in 2012, over 2,000 defenders around the world have been murdered. Yet governments fail to document and investigate attacks, let alone identify and tackle the root of the problem.

Defenders and their communities are exposed to an ever-evolving range of reprisals, many of which are hidden from view. Or worse, ignored.

When I look at my country, so rich in resources yet so unequal, I can clearly see that natural resource extraction is oppressing rather than supporting citizens. The exploitation of people and the environment has its roots in colonial violence, racism, and injustice.

Our ancestors understood the power of informing, educating, and mobilising people. And they made history by putting such power to use.

Knowing my life is in danger every day is deeply taxing. And I know I am not alone

Nonhle Mbuthuma, 2024 Goldman Prize Winner and founder of the Amadiba Crisis Committee

Now it is my role, as a defender, to push elite power to take radical action that swings us away from fossil fuels and towards systems that benefit the whole of society.

It is the job of leaders to listen and make sure that defenders can speak out without risk. This is the responsibility of all wealthy and resource-rich countries across the planet.

So, every time I am told about the benefits of multinational corporations operating in my country, I always ask: once the ocean has been polluted, once our livelihoods have been destroyed and the inequality gap widened, once irreversible damage has been done, who is going to pay the price?

Today, we are in a climate emergency. And in many ways, we’re still having to fight for the same basic things: our fundamental rights. Defying this status quo is a collective challenge for our future and for the future of our shared world.

That is precisely why we will keep fighting. It is why we will not be silenced. It is why we will keep making history.

Julia Francisco Martínez stands at the graveside of her husband Francisco Martinez Marquez, an Indigenous activist found murdered in Honduras in January 2015 after months of death threats. Giles Clarke / Global Witness

Every year, land and environmental defenders around the world are murdered for daring to resist environmental exploitation. In 2023, we documented 196 defender killings.

The global perspective: 2023 key findings

Global Witness documented that 196 defenders were murdered in 2023 after exercising their right to protect their lands and the environment from harm. The actual number is likely to be higher. This tips the total number of killings to over 2,000 globally since Global Witness started reporting data in 2012. Global Witness estimates that the total now stands at 2,106 murders.

Murder continues to be a common strategy for silencing defenders and is unquestionably the most brutal.

But as this report shows, lethal attacks often occur alongside wider retaliations against defenders who are being targeted by government, business and other non-state actors with violence, intimidation, smear campaigns and criminalisation. This is happening in every region of the world and in almost every sector.

Murdered defenders were, in different ways, trying to protect the planet and to uphold their fundamental human rights. Every killing leaves the world more vulnerable to the climate, biodiversity and pollution crises.

Over 1,500 defenders have been murdered since the adoption of the Paris Agreement on climate change on 12 December 2015.

Latin America

Latin America consistently has the most documented murders of land and environmental defenders – 85% of cases in 2023.

Lethal attacks against defenders were concentrated in four key countries that accounted for more than 70% of murders: Brazil, Colombia, Honduras and Mexico. Global Witness has warned about this trend in the region for many years.

Of those murdered in 2023, 43% were Indigenous Peoples and 12% murdered were women.

Colombia is the world’s deadliest country for land and environmental defenders, with 79 murdered in 2023 – 40% of all reported cases. This is the highest annual total for any country documented by Global Witness since we began documenting cases in 2012.

In just over a decade, 461 defenders have been murdered there; Colombia now has the highest number of killings documented between 2012 and 2023.

A total of 31 of those killed in Colombia in 2023 were Indigenous Peoples and six were members of Afrodescendant communities.

Many families have been disproportionately affected by armed conflicts, land disputes, and human rights violations exacerbated by over half a century of armed conflict.

The overwhelming majority of attacks are in the southwestern regions of Cauca (26), Nariño (9) and Putumayo (7). A mix of coca cultivation, drug trafficking and armed conflict has devasted these regions, with defenders and communities often caught in the crossfire.

Organised crime groups are suspected to be the perpetrators of half of all defender murders in Colombia in 2023.

It has only been possible to establish links between attacks on Colombian defenders and the industries sparking community activism in a handful of cases: five related to mining, three to fishing, one to logging and one to hydropower.

While the government of President Gustavo Petro has made commitments to reduce violence, these have not yet led to a decrease in reprisals against some of the country’s most vulnerable activists and communities.

On the contrary, violence against human rights defenders and social leaders appears to be increasing, with the Colombian organisation Programa Somos Defensores reporting no significant improvement in overall trends.

The Colombian government has a historic opportunity to address these challenges as the host of the Convention on Biological Biodiversity (CBD COP), which will be held in October 2024.

The Convention on Biological Diversity and how it can help protect defenders

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) is the international legal instrument for "the conservation of biological diversity”. The CBD’s governing body is the Conference of the Parties (COP), which meets every two years. In 2024, Colombia will host the CBD COP16 in Cali.

An important outcome of CBD COP negotiations is the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which was adopted by parties in 2022. The GBF sets out an ambitious pathway to achieve harmony with nature by 2050 with specific recognition of the need to fully protect environmental human rights defenders.

Target 22 commits to “the full, equitable, inclusive, effective, and gender-responsive representation and participation” of defenders in decision-making. It also recognises the cultural, territorial and resource rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities to access justice and information related to biodiversity.

Environmental defenders, and in particular Indigenous Peoples, play a vital role in protecting biodiversity, defending climate-critical forests, habitats and ecosystems. Across 90 countries, they steward more than a third of the Earth’s protected land and preserve an estimated 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity.

Research shows that Indigenous-managed lands have lower deforestation rates and better conservation outcomes than protection zones that exclude Indigenous Peoples.

The Colombian government has committed to placing environmental defenders at the centre of COP16. The Colombian Minister of Environment, Susana Muhamad, has stated that the theme of COP16 will be "Peace with Nature", which seeks to highlight the voices of those who are taking care of the biodiversity and the territories.

Colombia will have the CBD presidency for two years until the next COP in 2026. This presents them with a unique opportunity to lead transformational change on the role environmental defenders and civil society play at COPs.

Óscar Eyraud Adams is remembered by his family at a ranch in Juntas de Nejí, Baja California, Mexico. A prominent Kumiay Indigenous activist, Óscar was shot and killed at his home in September 2020. Luis Rojas / Global Witness

Similar trends are evident in Mexico and Honduras, with 18 defenders killed in each country in 2023 – down from 31 in 2022 in Mexico, and up from 14 in Honduras.

In Mexico, over 70% of defenders murdered in 2023 were Indigenous Peoples, with a concentration of attacks along the Jalisco-Colima-Michoacán Pacific coastal states – a majority of these opposed mining operations in the region. Out of the three states, Michoacán was the deadliest with eight murders documented in 2023.

In contrast with Colombia, we were able to connect over 40% of killings in Mexico in 2023 to defenders opposing mining operations. The mining sector continues to play a pivotal role in the country, contributing significantly to the nation’s economic landscape.

Beyond murders, Mexico has also experienced a significant number of enforced disappearances, a particularly vicious form of violence typical, though not exclusive, to this country.

With the same number of murders as Mexico but less than a tenth of population, Honduras emerged as the country with the most killings per capita in 2023.

The Honduran organisation ACI-Participa has identified the lack of productive lands for farmers, the prioritisation of extractive activities and the violation of the rights of Indigenous and Afrodescendant Peoples as key to understanding the prevalence of the attacks in the country.

Overall, attacks in Brazil are down from 34 in 2022 to 25 last year. Over half were Indigenous Peoples and four were Afrodescendants.

The incoming president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, faced high expectations to reform regressive policies introduced by his predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro, whose presidency was characterised by laws that opened the Amazon to exploitation and destruction.

These policies have fuelled illegal invasions of Indigenous lands and weakened the country’s plans for cutting emissions.

So far, there has been progress. The government has restored funding to protect the Amazon and reinstated the Indigenous affairs agency that Bolsonaro dismantled.

Yet policy changes remain challenging in the face of a conservative Congress dominated by ruralistas, who support the interests of private landowners over public agrarian reform.

In 2023, Global Witness documented at least 10 murders related to “landless peoples”, part of the landless peasant movement demanding more equitable land distribution.

The Brazilian organisation Comissão Pastoral da Terra has been reporting an increasing number of conflicts related to land over the last decade, with 2023 marking an all-time high.

Asia

In Asia, 468

defenders were murdered between 2012 and 2023 – 64% in the Philippines (298),

with additional cases in India (86), Indonesia (20) and Thailand (13). In 2023,

we recorded killings in the Philippines

(17), India (5) and Indonesia (3).

Jonila Castro takes part in an Independence Day Protest in Manila, Philippines, June 2024. Her and fellow climate activist Jhed Tamano have campaigned against large land reclamation projects in Manila Bay. Raffy Lerma / Global Witness

Non-lethal attacks are also increasingly used as tactics to suppress activism across the region. Forum Asia identified judicial harassment as the most recorded violation against human rights defenders in Asia in 2021 and 2022, documenting 1,033 incidents.

Global Witness has reported seven enforced disappearances in the Philippines, with the trend appearing to extend to other countries in 2024.

The abduction of land and environmental defenders in Southeast Asia has emerged as a critical issue, reflecting broader systemic efforts by power holders to suppress dissent and maintain control over land and resources.

A stark example is the recent abduction of Muhriono, a farmer from Pakel, Banyuwangi, East Java. This incident underscores the growing trend of targeting individuals who challenge powerful interests, particularly those linked to land rights and environmental protection.

The Philippines is the most dangerous country in Asia for defenders

Africa

In Africa, two

defenders were murdered in the Democratic Republic of Congo, one in Rwanda and

one in Ghana in 2023. Between 2012 and 2023, 116 defenders were murdered in

Africa, most of them park rangers in the Democratic Republic of Congo (74).

We

have also documented cases in Kenya (6), South Africa (6), Chad (5), Uganda (5),

Liberia (3) and Burkina Faso (2), among other countries.

These chilling figures

are most likely a gross underestimate as access to information continues to be

a challenge across the continent.

Malungelo Xhakaza holds a photograph of her mother, Fikile Ntshangase, who was killed in 2020 after opposing the expansion of a coal mine bordering the community of Somkhele, South Africa. Thom Pierce / Global Witness

Contested civic space

In Europe and North America, defenders are also facing increasingly difficult situations as they exercise the right to protest. There, too, civic space is increasingly contested.

Four demonstrators were killed in Panama last year, while two were killed in Indonesia.

In the United States, a police officer shot dead an environmental defender who was demonstrating against the destruction of a local forest to make way for a police training complex.

Manuel Paez Terán was killed by police gunfire during a peaceful protest against the destruction of a forest threatened by the construction of a controversial "Cop City" police training facility in Atlanta, US. Washington Post / Elijah Nouvelage / Getty

People and communities

In 2023, the disproportionate number of attacks continued globally on Indigenous Peoples (85) and Afrodescendants (12).

This includes attacks against representatives of some communities who have been fending off land invasions, often with little or no state support. It also includes those who have been trying to engage constructively with corporate interests to ensure their lands are not destroyed or polluted.

In some cases, the relatives of activists are targeted or caught up in violence. Though these cases of lethal attacks are less common, a third of these attacks in 2023 were against women relatives. Women defenders also face additional challenges and specific gendered risks, including when they defy traditional gender norms.

These types of punitive attacks highlight the patriarchal nature of violence against defenders, signalling the need for justice that addresses intersecting forms of oppression.

Industry drivers

Establishing a direct relationship between the murder of a defender and specific corporate interests remains difficult. However, we were able to identify mining as the biggest industry driver by far, with 25 defenders killed after opposing mining operations in 2023.

Mining was the biggest corporate driver of defender killings in 2023

More than 50% of mining-related killings between 2012 and 2023 were in Latin America. Last year, 23 of the 25 mining-related killings globally happened in this region.

Over 40% of all mining-related killings have occurred in Asia between 2012 and 2023. The region has significant natural reserves of key critical minerals vital for clean energy technologies, including nickel, tin, rare-earth elements and bauxite.

This might be good news for the energy transition, but without drastic changes to mining practices it could also increase pressure on defenders.

The trends behind attacks in Central America

Together,

the seven countries that make up Central America – Belize, Costa Rica, El

Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama – are roughly the same size

as Thailand. Yet this small area contains 12% of the world’s biodiversity.

This richness extends to the region’s cultures. Central America is home to numerous Indigenous Peoples and Afrodescendant communities, whose collective knowledge and practices could play an essential role in addressing climate change.

However, their voices have been systematically sidelined from climate decision making, an echo of colonial structures that have historically disregarded Indigenous knowledge.

Today, this knowledge is needed more than ever. With its patchwork of tropical ecosystems covering a narrow strip between the Pacific and Caribbean coastlines, Central America is highly vulnerable to climate change.

It is also under increasing threat from destructive industries. Of its lush vegetation, 80% has already been converted to agricultural land, fragmenting climate-critical forests and driving biodiversity loss.

A palm oil plantation in Guatemala. Central America has for decades been subject to unsustainable extractive activities, including logging, mining, energy projects, and monoculture plantations. Graeme Kennedy / Getty

Where nature, land and ecosystems are threatened, so too are defenders and their communities. This is especially true in Central America. For just over a decade, defenders in this region have endured more attacks per capita than anywhere else in the world – with 97% occurring in the same three countries: Honduras, Guatemala and Nicaragua.

In 2023, the threat was even more acute: 36 defenders were killed in Central America, almost one in five of the killings we documented globally, in a region with less than 1% of the world’s population.

Almost half of those killed in Central America in 2023 (17) were Indigenous defenders. Two were Afrodescendants and eight were small-scale farmers. In one of the murders in Honduras, a 15-year-old was killed alongside his defender father.

Relatives and friends mourn teachers Iván Mendoza and Abdiel Díaz, who were shot during a protest against a Canadian mining company in Panama, 2023. Roberto Cisneros / AFP

Recent research has also shown that, between 2012 and 2023, over 9,000 women human rights defenders were the subject of attacks across Central America and Mexico. Almost half of those attacks were perpetrated by the state, often acting to protect the interests of extractive industries and organised crime.

All in all, 314 defenders were murdered in Central America between 2012 and 2023. Of those, over a half (161) were Indigenous Peoples and 18 were Afrodescendants.

Faced with such figures, it is essential to ask why some countries in Central America are so dangerous for those who seek to protect the planet – particularly for Indigenous communities.

Authoritarianism and impunity

Authoritarian regimes provide political and economic elites with impunity to use violence to maintain corrupt networks and ensure control over natural resources.

Northern Nicaragua contains the second-largest rainforest in the western hemisphere, the Bosawás. The area is also home to two of Nicaragua’s most vulnerable Indigenous Peoples, the Mayangna and Miskito.

All 10 murders Global Witness registered in Nicaragua in 2023 were of Indigenous Peoples, as were 69 out of the 70 cases documented between 2012 and 2023.

In recent years, Nicaragua has been losing forest more quickly than anywhere else in the world, and the Mayangna and Miskito have endured repeated massacres.

This devastation is "facilitated and permitted" by the Nicaraguan government, according to human rights groups, with one think tank calling the "systematic murder" of Indigenous Peoples "an unstated policy of the Nicaraguan state aimed at appropriating their lands.”

At the same time, victims of state violence have no access to justice in Nicaragua, where hundreds were killed in a crackdown on protesters demanding democratic reforms in 2018.

Since then, thousands of NGOs and community groups have been forcibly closed, making it close to impossible for civil society to organise to defend their rights.

Forced evictions of communities in Honduras are often connected to land disputes and narco-trafficking. Honduras has the highest murder rate per capita of defenders globally. Spencer Platt / Getty

Organised crime and corruption

Since the mid-2000s, Central America has been a key transit point in drug trafficking routes from South America to markets in the United States (US) and Europe. This strategic location, combined with wider militarisation and drug crackdowns, forces traffickers into the shadows, putting defenders at immense risk.

Drug prohibition policies have failed to reduce global drug flows and instead driven traffickers deeper into forests and remote areas. Once there, they transform ecologies and terrorise local communities, creating landing strips and roads to move shipments, as well as carving out cattle pasture to launder money.

Laws that protect Indigenous and community rights to land and sovereignty are vital to increase local resilience against organised criminal gangs.

The economic might of drug trafficking groups also undermines governance more broadly, however. Part of their revenue is reinvested in corruption to buy impunity and smooth the flow of narcotics.

The resulting corrosion of the institutions that should enforce environmental laws, and of the justice system that should guarantee accountability for harms, further escalates the risks faced by defenders and undermines efforts to protect them.

Honduras is the deadliest country in Central America

An extreme example of this is Honduras, which frequently ranks among the most dangerous countries in the world for defenders in terms of per capita killings. In March 2024, the country’s former president, Juan Orlando Hernández, was found guilty of conspiring to import cocaine into the United States.

Hernández served as president from 2014 to 2022, much of this time with enthusiastic US backing. Prosecutors argued that Hernández had turned Honduras into a “narco-state” where the tendrils of corruption reached into the highest echelons of power.

Historic conflict and militarisation

Several countries in the region, including Guatemala and Nicaragua, have been devastated by long and bloody civil wars.

These conflicts go back to the Cold War. In 1954, Guatemala was plunged into dictatorship after a CIA-engineered coup killed its fledgling democracy. Six years later, the country was engulfed by a civil war that raged for the next 36 years.

At its height, government forces committed acts of genocide against five Mayan Indigenous groups, according to an UN-backed truth commission.

The civil war left key Guatemalan institutions controlled by criminal networks with close ties to its powerful military. These groups continue to exert huge influence today.

In the last four years, more than 50 human rights defenders, prosecutors, judges, anti-impunity advocates and journalists have been forced to flee the country due to unfounded criminal proceedings initiated against them by the country’s Prosecutor’s Office.

Many of the criminal complaints used to attack those leading the fight against impunity were filed by a far-right NGO, the Foundation Against Terrorism, run by the son of a military general allegedly implicated in wartime atrocities.

Private security guards the Agua Zarca dam in Honduras. The dam's head of security was among seven arrested for the murder of Indigenous defender Berta Cáceres, killed at home after years of threats. Giles Clarke / Global Witness

Corporate exploitation

Compounding all this, Central America has for decades been subject to unsustainable extractive activities, including logging, mining, energy projects, and monoculture plantations.

Again and again, multinational corporations have colluded with predatory national elites to run roughshod over community rights and consultation procedures. Communities that have resisted and sought to defend their lands and resources have faced violent repression and death.

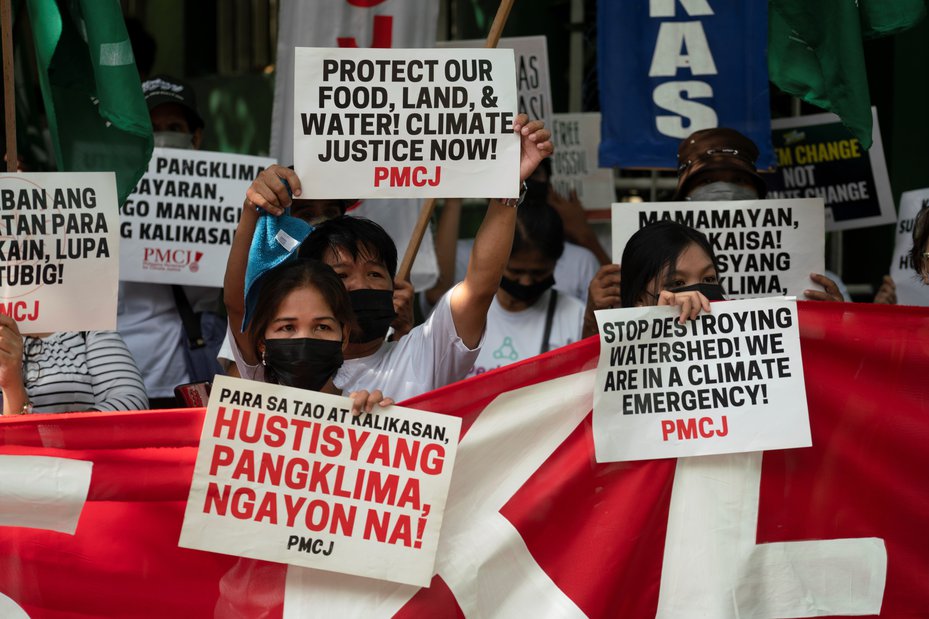

In 2023, events in Panama vividly demonstrated this reality. Plans to award a new contract to a Canadian-owned copper mine deep in the Panamanian forests sparked nationwide protests that lasted for over a month and brought the country to a standstill.

Protests were led by Indigenous groups, unions and citizens concerned about pollution, deforestation and water shortages.

The mine was portrayed as a flagship project that would boost the local economy. But it proved catastrophic and was shut down by the Supreme Court. It also had tragic consequences: four defenders were killed in the crackdown against protests, two crushed by vehicles and two shot at point-blank range.

A demonstrator protests a controversial copper mining project in Panama City, 2023. The protests, which spanned several months, claimed the lives of four environmental defenders. Roberto Cisneros / AFP

The devastating impacts for Indigenous Peoples and local communities when consultation processes are bypassed have been widely reported for years.

As the world speeds up efforts to transition away from fossil fuels and rushes to extract the metals required for the green economy, it is essential to ensure we are not repeating the same mistakes from the past.

All the examples above illustrate the deep systemic reforms required to make Central America safe for defenders. Without functioning institutions, effective governance and basic rule of law, any progress in this troubled region will remain piecemeal, fragile, and easy to reverse.

Building such foundations requires fundamental change, including a move away from the war on drugs, which has channelled huge wealth and influence into the hands of criminal actors, generating rampant corruption and impunity while failing to stem the flow of narcotics.

Efforts to achieve such a shift are gaining traction, with UN human rights experts, Amnesty International, and politicians at both ends of the narcotics supply chain calling for reform. Civil society, policy advocates and others concerned with human rights in the Americas must unite to support this sea change.

Another opportunity to generate change is the Escazú Agreement – the first regional environmental and human rights treaty in Latin America and the Caribbean – a legally binding instrument which includes provisions on environmental defenders.

Entering into force in April 2021, the Escazú Agreement aims to guarantee the public the right to access environmental information and participate in environmental decision-making. Most significantly, it also requires states to prevent and investigate attacks against environmental defenders.

So far, five countries in Central America have signed the agreement, while three have ratified. Despite having the highest number of attacks per capita, Honduras is yet to sign.

As well as commitment from all countries in the region, more must be done to ensure the agreement is implemented effectively and enforced robustly at the national level.

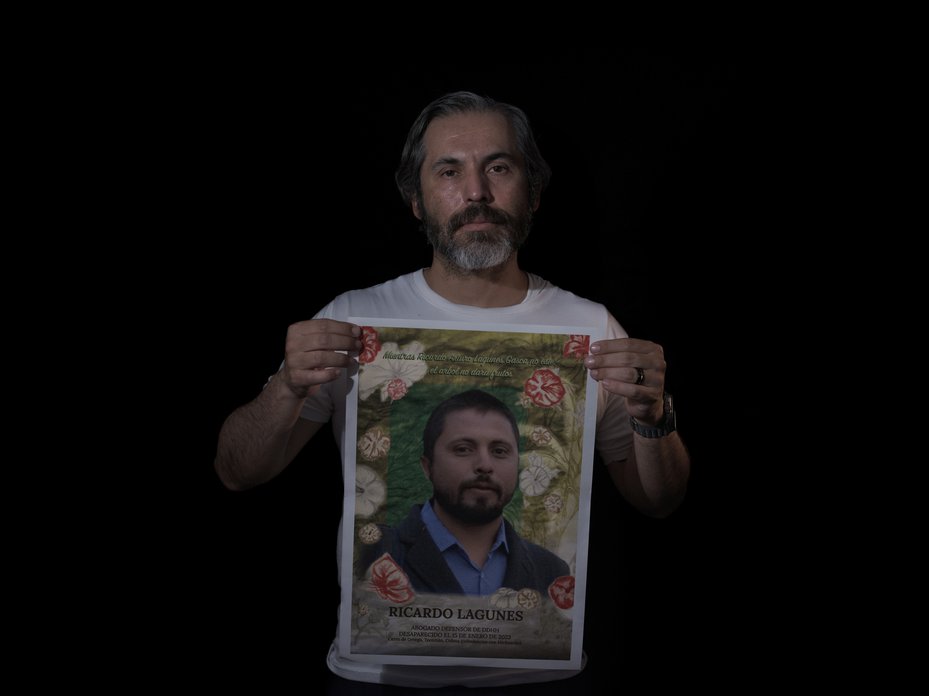

Family members sift through photographs of Ricardo Arturo Lagunes Gasca, a human rights lawyer who disappeared with Indigenous leader Antonio Díaz Valencia after attending a community meeting in San Miguel de Aquila, Mexico. Luis Rojas / Global Witness

Enforced disappearances represent a particularly cruel form of assault on defenders, leaving families in a state of perpetual uncertainty and denial of justice.

Stuck in limbo: Confronting impunity and enforced disappearances

Ricardo Lagunes and Antonio Díaz had been working together to protect the community of San Miguel de Aquila in Mexico from years of abuses by the mining giant Ternium. In January 2023, both defenders were forcibly disappeared. Neither have been found.

Nestled in the mountainous state of Michoacán, San Miguel de Aquila is surrounded by pine and oak forests that stretch all the way to the Pacific Ocean. But the real wealth lies underneath the surface: these mountains contain huge amounts of iron ore.

Decades of extraction have turned Michoacán into one of the most dangerous places in Mexico. At least 21 land and environmental defenders were forcibly disappeared or murdered in Michoacán between 2012 and 2023.

Relationships between communities and Ternium – one of the biggest steel producers in Latin America – are strained, and are further compounded by the presence of organised criminals and narcotraffickers fighting for territorial control.

There is a lot at stake: steel production is hugely profitable, netting the mining company global sales of US$ 17.6 billion in 2023 alone.

Enforced disappearances: the real-life implications for

defenders

The United Nations International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, which entered into force in 2010, defines an enforced disappearance as “the arrest, detention, abduction” or other “deprivation of liberty” by “agents of the state or by individuals or groups acting with the authorisation, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which place such a person outside the protection of the law.”

This seemingly formulaic definition hides an excruciating legal limbo. Families of forcefully disappeared defenders face absolute uncertainty about whether the person is alive or dead, and that determines what the family can or cannot do.

Uncertainty often also extends to whether official investigations are under way. The disappearance of Ricardo and Antonio vividly illustrates that the more the families try to find out about official investigations, the more elusive information becomes.

In the words of Antoine, Ricardo’s brother: “We have tried to break this silence that seems to surround disappearances, but it is proving really hard.”

Antoine Lagunes holding a picture of his brother Ricardo Lagunes who disappeared alongside Antonio. Luis Rojas / Global Witness

Mining profits come with huge costs to the environment and the climate. Large open-pit mines and enormous amounts of water and fossil fuels are needed to extract iron ore and manufacture steel. Overall, the steel industry contributes to around 8% of global carbon emissions.

Yet global demand for steel has been growing and is expected to increase, even as the world debates the environmental cost of the metals used in the green transition.

Ternium – incorporated in Luxembourg and a subsidiary of Italian-Argentinian group Techint – began its Michoacán operations in 2005. For years, the community expressed discontent with the way Ternium operated, protesting against environmental impacts and the very limited benefits the community received from the mining operations.

In Aquila, Mexico, Ternium’s extensive mining operations are reshaping both the environment and local community. Mining has fuelled inter-communal conflict and the presence of organised crime in the region. Heriberto Paredes

By the time operations expanded in 2019, Antonio Díaz had grown increasingly frustrated. A respected leader and a teacher, he had spent years trying to make sure the Las Encinas mine – which produces 1.9 million tonnes of iron pellets a year – was benefitting the community, and that Ternium was respecting the agreements it had made.

Concerned about its impact on the environment, on communities and on livelihoods, Antonio, on behalf of the majority of community members, called leadership elections to establish a legitimate agrarian authority.

This would provide them with more legal recognition and enable them to defend their land rights and re-negotiate the conditions under which the mine operated.

In addition, crucially, the intention was to put an end to years of conflict among community members – conflict that Ternium claimed were internal community conflicts, but which community members say have been caused by the company’s undue interference in the community’s life.

The expansion of the mine further fuelled inter-communal tensions, and it was then that Antonio decided to team up with renowned Mexican human rights lawyer Ricardo Lagunes to challenge the legitimacy of the unofficial representatives of the Nahua community.

Both knew the dangers of doing so. Ricardo had already faced threats to his life, according to witnesses, because of his work protecting Indigenous rights. As a result of previous work defending Indigenous lands in the states of Chiapas and Oaxaca, the Mexican government had granted him protection measures under the Defenders Protection Mechanism.

Defending human rights impacted Antonio and Ricardo, as well as their families and other community members who supported their work. For the next four years, they were followed and threatened by armed men.

During a community assembly in December 2022, with company managers present, Antonio and Ricardo allegedly received threats that they would be forcibly disappeared if they continued to speak out against Ternium.

In a letter sent in December 2022 to the then Mexican president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Antonio accused Ternium of paying armed groups to attack and repress members of the Aquila community.

Despite these challenges, the community renewed efforts to re-elect a new community agrarian authority and renegotiate royalty agreements.

A month later, Antonio and Ricardo were taken. On the evening of 15 January 2023, their car was found abandoned with flat tyres in Colima, near the border state with Michoacán. They had been returning from a community meeting when they were attacked.

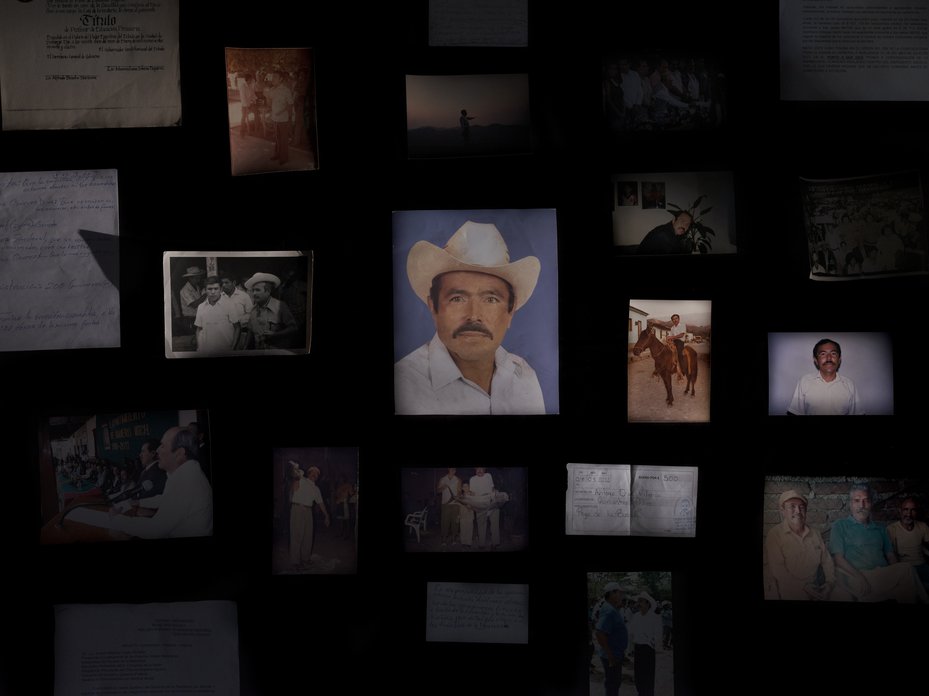

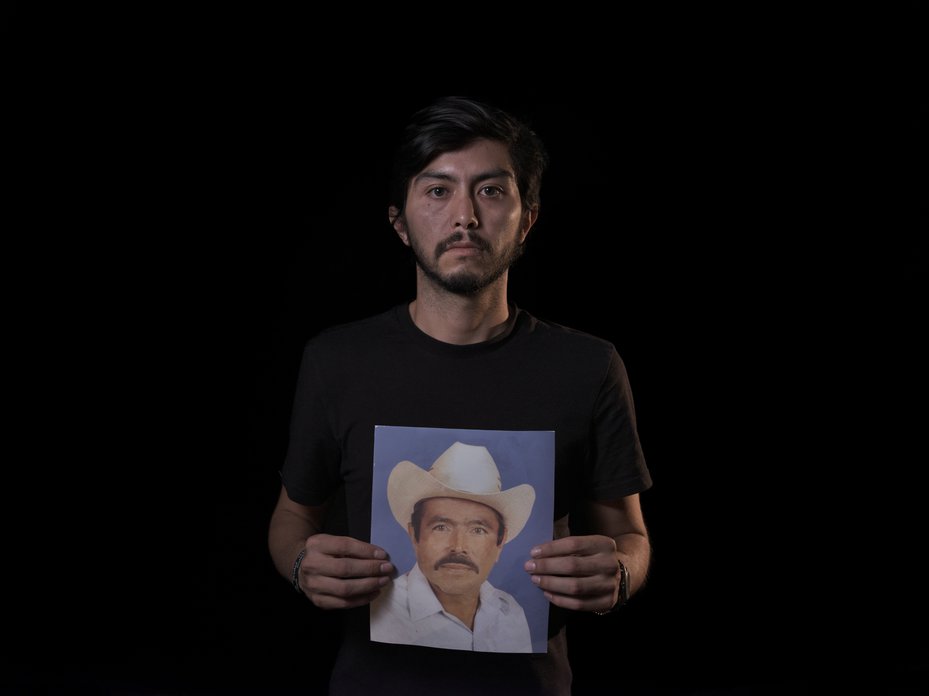

Personal photographs and documents of Antonio Díaz. Luis Rojas / Global Witness

For over a year, their families have been desperately trying to find them – but nobody seems to know anything. The Mexican Prosecutor’s Office has failed to pursue their work as land and environmental defenders as an avenue of investigation linked to the disappearance.

“They haven’t given us any information about my brother, it has been torture for us,” says Ana Lucía, Ricardo’s sister. “We are trying to carry on, to stay healthy so that we can continue, because we don't know how long it will take. We won’t stop looking for him – not for a second do we forget that he is not with us. And that they have done things to him. That is driving us crazy.”

The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has reported on Mexico’s failure to implement fully its specialised protocols for investigating disappearances of human rights defenders. This lack of action amplifies the impacts of impunity on the families and their anxiety and fear.

It is like Mexico swallowed them. That's how I put it, they just vanished

Keivan Díaz, Antonio Díaz's grandson

The disappearances of Ricardo and Antonio are not the first attacks against community defenders and Indigenous leaders opposing mining activities in Michoacán.

In November 2013, three Aquila community representatives were forcibly disappeared after submitting a complaint to local agrarian authorities that accused Ternium of failing to comply with their agreement. Months later, their bodies were found.

Recent research has shown that, across Mexico, 93 land and environmental defenders were disappeared between 1 December 2006 and 1 August 2023. Over 40% of them have still not been found.

Ternium has pointed out the deterioration of wider security in Aquila, where Las Encinas has its main mining operation, blaming worsening violence on the territorial expansion of organised criminals looking to exploit economic resources.

Iron ore extracted from illegally run mines in Michoacán and the neighbouring state of Jalisco has been fattening the profits of organised crime. Royalty payments received by the Nahua community have been subject to extortion, with many in the community blaming Ternium for revealing details about payments and putting their safety at risk.

The risk is so high that the Nahua community has established a community police force to better protect itself.

Keivan Díaz holding a picture of his grandfather, Antonio Díaz, who was disappeared in 2023. Luis Rojas / Global Witness

“The forcible disappearance of Ricardo and Antonio is directly linked to their work as human rights defenders,” Antoine asserts. “Both the government and organised crime played a role in it."

The situation has not improved since Ricardo and Antonio disappeared. Three months after they vanished, the anti-mining activist Eustacio Alcalá also disappeared, and was found dead two days later.

Eustacio was an Indigenous Nahua leader in San Juan Huitzontla, 20 km from San Miguel de Aquila, who also opposed the Las Encinas mine. His community had filed a writ of protection against six mining concessions granted to two mining companies – one a subsidiary of Ternium.

There is no hard evidence that Ternium or its employees have ordered or carried out any forced disappearance of land defenders. The presence of vast iron ore mining in the region has contributed to a microcosm of competing interests including the territorial expansion of organised criminals and worsening violence.

Ana Lucía Gasca Boyer (Ricardo’s mother) embracing a loved one at a protest to remember the disappeared, Mexico City, 2023. Luis Rojas / Global Witness

The long-term impact of disappearances is hard to overstate. Eliminating leaders like Antonio without trace sows fear, paralysing entire communities, which can take generations to recover. Cutting off legal support by attacking lawyers like Ricardo reduces legitimate avenues for land and environmental defenders to seek reparation.

Disappearances appear to be part of a wider arsenal used to deter communities from voicing their opposition to mining projects.

“A disappearance changes everything, destroys everything: your goals, your projects, your life”, says Antonio’s grandson Keivan Díaz. “The damage doesn't end with the disappearance. In fact, that is where it begins. I have been asking since day one where he is, what happened to him, what happened to Ricardo. That’s all I want to know”.

Antonio’s daughter, Brenda, shares that feeling. “I wish the world could see the destruction mining causes in Aquila – to our environment, to us. I wish they could see how the water in the river has disappeared, just as my father and Ricardo have. Ternium is a world leader in iron mining, and it is a powerful force in Mexico. They should be using that power to bring them back”.

There are countless stories of defender courage we want to tell but can’t.

Around the world, those who oppose the abuse of their homes and lands are met with violence and intimidation. Yet, the full scope of these attacks remains hidden.

Many killings go unreported. Fear of retaliation keeps families from seeking justice, and communities are coerced into silence. Journalists become targets. Stories are buried, covered up, erased.

Often, we have very little information about a case at all. Many defenders will remain unnamed, their sacrifices unacknowledged, their stories of defiance untold.

A disturbingly small percentage of cases result in perpetrators being held accountable. Families may never find justice or closure, nor feel safe enough to speak out. The truth is obscured by a system of complicity: compromised civic spaces, rampant corruption and dysfunctional legal systems.

Erasure is a form of attack too.

We will continue to fight against the systemic silencing of land and environmental defenders and their vital work.

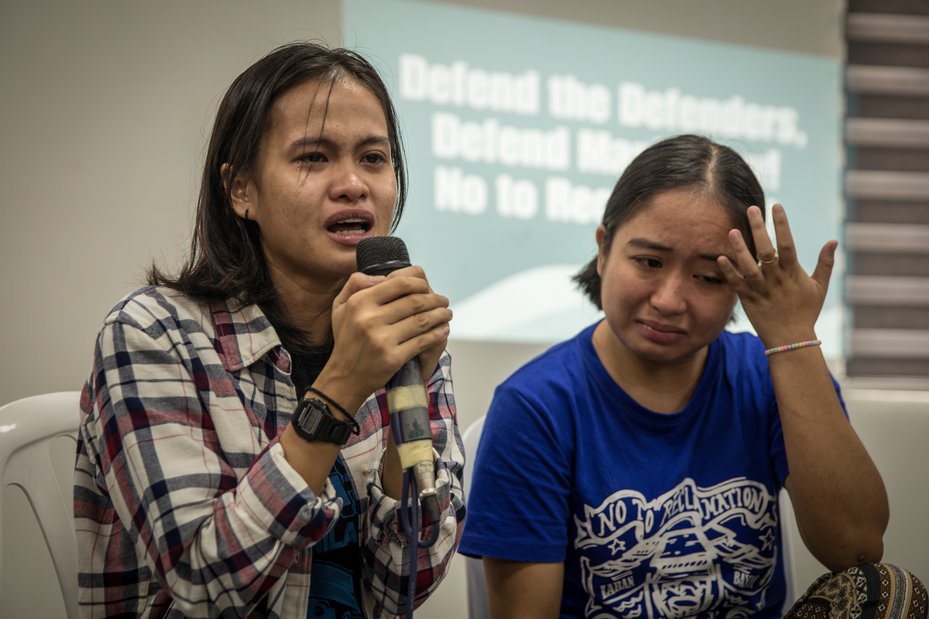

Jonila Castro is released and consoled by friends following their abduction and detention allegedly by the Philippine military for a total of 17 days in September 2023. Raffy Lerma / Global Witness

Governments and other actors across Asia are using abductions as a means of silencing and intimidating those who speak out against corporate harm.

Fabricated lies and forced confessions: Silencing defenders in Asia

Jhed Tamano and Jonila Castro are youth environmental advocates who live in Manila Bay, the Philippines.

Jhed, 22, is a coordinator of the community and church program for Manila Bay of the Ecumenical Bishops Forum, and Jonila, 23, is an advocacy officer for reclamation and water at Kalikasan’s People’s Network for the Environment.

Both women are known for their opposition to massive land reclamation projects in Manila Bay, including the construction of the US$15 billion New Manila International Airport.

The airport project has displaced hundreds of families, destroyed climate-critical habitats and devastated wildlife, as Global Witness reported in 2023.

On 2 September 2023, while Jhed and Jonila were working with fisherfolk communities, they were violently abducted by armed men.

The military are suspected to have been involved in their abduction.

Across Asia, governments are increasingly using such tactics to silence and intimidate people who speak out against corporate harm. Jhed and Jonila described their experience in their own words.

Being abducted reminded us of our strength. We are more determined than ever to fight injustice

Jhed Tamano and Jonila Castro, youth environmental advocates

“The press conference was packed. Mainstream media and renowned radio stations had all come to see us. Some of our colleagues and supporters were outside the venue too – they had not been allowed in. Nobody could quite believe we were still alive, and neither could we. We had been missing for 17 days.

"But that conference was a set up. The government, our kidnappers, had organised it so we could publicly confess to being communist rebels – even though we were not. We had been given a couple of pages with the 'official' story we were expected to tell and the answers we were expected to give.

"Instead, we told the truth.

Jonila Castro, 21 (left), and Jhed Tamano, 22 (right), were advocating for coastal communities opposing reclamation activities in Manila Bay when they vanished on 2 September, 2023, near the capital, Manila. Raffy Lerma / Global Witness

"And the truth is that it rained on 2 September. We were into our second month as volunteers and had gone to visit fisherfolk communities impacted by new projects in Manila Bay. We witnessed the many ways that land reclamation activities – the deliberate process of making landbanks in bodies of water by filling them with sand and other materials – were devastating people’s livelihoods and the surrounding environment.

"We had spent time with concerned fisherfolk who wanted to raise awareness but were worried about speaking out. We understood why they were concerned, as both of us had been targeted for what we did. The military and the government anti-communist agency had visited one of our homes and threatened our families.

"For a couple of weeks, we were certain that a handful of men had been quietly watching us and asking about us. One of them had gone as far as taking our picture without our consent. But now we were in the community, and we were feeling good about our work.

"The rain made us decide to stay and eat with community members. It was getting late by the time we said our goodbyes and started to walk across a bridge to our next destination.

We felt a chill when we realised it was the same man who had taken our photo. Women everywhere know the fear of being followed

Jhed Tamano and Jonila Castro, youth environmental advocates

"We later learned that the man who had taken our photo was standing by the bridge. He had been following us. We felt a chill when we found this out; women everywhere know the fear of being followed.

"After walking for a few minutes, everything happened really quickly. A car pulled up next to us and four armed men forced us into it. As we sped off, they searched our backpacks – yes, they really thought we might be armed! They blindfolded us, tied our hands, and taped our mouths.

"We tried screaming as loud as we could in the hope that someone might hear. It was then that one of our abductors threatened to punch us in the face if we didn’t keep quiet.

"It only took us a few minutes to figure out that these men were military. They knew too much: they knew our families, our addresses, and they kept saying all they wanted to do was bring us back to our 'normal lives', as if our current lives were dangerous – other than this moment. The irony of their remarks was clearly lost on them.

"We were taken to a so-called safe house, but we felt anything but safe. Everyone in the Philippines knows that 'safe houses' are code for secret detention facilities. It was there that the interrogations began, and it really felt like they would never end. We spent the evening there, terrified.

"The following morning, we were transferred to another location and separated.

Jonila Castro recalls the details of her and Jhed's abduction in an interview with Global Witness. Raffy Lerma / Global Witness

"We were subject to psychological torture, emotional blackmail and death threats. Our captors shifted from passive aggressiveness to full-blown hostility. They said they would cut our tongues. They said we were lucky not to have been sexually assaulted yet. They said they knew we had young relatives we loved.

"To us, though, the worst part was that they told each of us that the other had 'surrendered', had promised to stop our advocacy work, and was giving up the names of others who had spoken out.

"This is what communities in the Philippines fear. Being accused or called a communist terrorist is deadly. Neither of us believed it but we felt the pressure – and realised how possible it was to cave in. Fear and the instinct to survive kicks in.

"We didn’t though. We knew we had to make them believe we were cooperating. This was emotionally exhausting and incredibly stressful – we were anxious about what might happen to us if we were caught lying. But they believed us.

"It is strange to live with your abductors for so many days. You end up developing a complex relationship.

"Sometimes they were nice to us, asking what we might like to eat, asking why we got into activism. They would talk about their own families and aspirations. We almost felt pity for them. But we also knew the military are widely accused of abducting and murdering other fellow activists. So we were full of anger too.

"Our lives were in their hands.

We were determined to put an end to this machinery of lies, whatever the cost to our personal lives

Jhed Tamano and Jonila Castro, youth environmental advocates

"Each new day brought with it new uncertainties about what might happen. After 12 days of no contact with our families, colleagues or lawyers, we were transferred to a military camp, where we were finally reunited.

"This is when we started planning. We would communicate secretly while pretending to play sudoku, sharing notes with strategies we could pursue. We needed to get out of there first, so we agreed to sign an affidavit saying that we were surrendering to the government as rebels.

"Our captors wanted us to attend a press conference where we would be surfaced and forced to publicly confess our 'voluntary surrender'. They even proposed that we go to several schools and warn students that becoming activists would destroy their lives.

"We agreed to participate in the press conference. But with our plan in mind, we decided to tell the truth about what had happened. We both knew this was dangerous – we could be put in jail, or we could be taken back to the military camp and get killed.

The two young activists allege psychological torture, emotional blackmail, and death threats during their time in military detainment. Raffy Lerma / Global Witness

"But this felt like our only chance. And we were determined to put an end to this machinery of lies, whatever the cost to our personal lives.

"What we did not imagine is that we would walk out of that press conference as free women. That only happened because of the public support we received, and the outrage our abductions had caused. So many people interceded for us: there was a progressive congresswoman, a lawyer, a priest, and fellow defenders.

"There were also simultaneous protests outside the press conference venue and in several places across Manila. All of them stayed there for hours, demanding our release. It was such a victorious moment.

"At times hopelessness set in, but then we saw how much support we had, and the incredible power of collective action as a force for change.

The government is filing trumped-up and malicious charges against us in an attempt to prolong their intimidation tactics

Jhed Tamano and Jonila Castro, youth environmental advocates

"Since our release, the threats have continued. The government is filing trumped-up and malicious charges against us in an attempt to prolong their intimidation tactics. Our families and colleagues have been threatened and harassed. The impact on them has been immense.

"We have not been able to fully go back to the communities, and we know they are also under threat. All of Manila Bay is. These are the unseen impacts of attacks designed to shut down community activism.

"For us, the experience has been transformative, but perhaps not in the way it was intended. Rather than leaving this work and finding ourselves an easy job, this has renewed our resolve to continue protecting our planet.

"We are now more aware than ever that environmental plunder and human rights exploitation will carry on if we allow the current system to continue as usual.

"We can’t let that happen. We must hold onto our strength. And we have found that more than ever in collective action and justice. We are literally living proof that this is possible.”

We are now more aware than ever that environmental plunder and human rights exploitation will carry on if we allow the current system to continue as usual

Jhed Tamano and Jonila Castro, youth environmental advocates

In the Philippines, multiple activists have been abducted since President Ferdinand Marcos Jr took office in June 2022. This trend is part of the tactics used by authorities to intimidate people into silence.

While abductions are a common method of trying to silence environmental activists across the world, it is a lot less common for abducted activists to live to tell their stories, as Jhed and Jonila did.

The state’s relentless attempt to silence Jhed and Jonila is not over. In December 2023, the Department of Justice filed charges against them for oral defamation for “embarrassing and putting [the Armed Forces of the Philippines] in bad light” during the press conference.

Based on these charges, on 2 February 2024 a municipal trial court issued a warrant for their arrest. If found guilty, Jhed and Jonila may face up to six months in prison.

In August 2024, the Court of Appeals denied their petition for a protection order, further eroding protections for the two women, and defenders across the Philippines.

The decision overrides a previous ruling by the Supreme Court in October 2023, which granted both women temporary protection.

Protestors are confronted by police at the G7 Climate Meeting in April 2024, after taking a stand against government and corporate failures to meet key climate commitments. Stefano Guidi / Getty Images

Throughout 2023, the global surge in anti-protest legislation persisted, targeting individuals and groups involved in peaceful climate activism.

Defenders in the dock: Making an example of activists

Jhed Tamano and Jonila Castro’s case is just one example among a disturbing pattern of intimidatory tactics used against defenders. Across the world, governments are using laws to coerce and dissuade communities and individuals from protesting against the environmental crisis.

Criminalisation has become a key strategy to disempower and disrupt land and environmental movements, and is now the most common tactic used to silence defenders globally.

While legal contexts vary, the legal mechanisms governments and companies use follow a similar pattern, which includes enforcing laws designed to limit the civic freedoms of individuals and organisations.

Mexican police stand guard at a protest to remember victims of enforced disappearances, Mexico City, 2023. Luis Rojas / Global Witness

In recent years, a surge in new restrictive and draconian charges have been used to target peaceful protestors and activists, eroding their rights and disabling their ability to take part in climate action.

Between 2012 and 2016, more than 100 laws were proposed or enacted by governments with the aim of impeding the effective functioning of civil society organisations.

This trend has continued into the 2020s, with states imposing more restrictions on the ability of groups and individuals to organise, contesting civic space.

Laws designed to restrict the registration, operations and funding of civil society organisations have many consequences. Administrative and judicial harassment disrupts day-to-day work, limits resources, tarnishes institutions and erodes public trust.

In addition, several countries, including the United Kingdom and United States, have passed controversial anti-protest laws supposedly intended to protect national security or so-called critical infrastructure.

Equally concerning is the trend of using laws not typically associated with activism to maliciously target defenders, leading to charges such as subversion, illicit association, terrorism and tax evasion. All leave activists more vulnerable to attacks.

Stifling protest in the European Union, the United Kingdom and the United States

Governments worldwide are also taking action to suppress protest rights. Civic freedoms are under fire in the EU, the UK and the US, with activists increasingly facing legal action from both corporations and governments for taking part in peaceful protests.

Thousands of protestors were forcefully dispersed by police with batons and water cannons in the German village of Lützerath after protesting against the expansion of a coal mine in January, 2023. Sean Gallup / Getty

In the UK, a twin legislative and judicial clampdown on peaceful climate protesters is under way, with the former British government introducing a series of regressive new laws that facilitate the criminalisation of climate activists.

Introduced in April 2022, the UK Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act gives the police broad powers to limit the right to protest, including the ability to criminalise one-person protests and powers to arrest demonstrators deemed to be making too much noise.

This law also establishes the offence of “intentionally or recklessly causing public nuisance” – punishable by up to 10 years in prison.

Between the law’s introduction and the end of 2022, the Crown Prosecution Service had issued at least 201 charges of statutory public nuisance aimed at individuals participating in protest action.

This has a significant chilling effect on civil society and the exercise of fundamental freedoms

Michel Forst, UN Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders

Just over a year later, the UK government expanded restrictions through the Public Order Act, granting police extensive powers to criminalise peaceful protests that disrupt key national infrastructure, such as slow marches on public roads.

The Act also granted the police nearly limitless authority to suppress any protest deemed to cause “more than a minor” disturbance.

This broadened authority has led to the criminalisation and arrest of hundreds of protesters.

In the UK, in November 2023 alone, police made at least 630 arrests for peacefully "slow marching" against new oil and gas projects. The Metropolitan Police arrested more than 5,975 climate activists between 2019 and 2022, records show. In 2023, there were 1,029 arrests, 897 of them for slow marching.

Growing numbers of environmental protesters are also being handed jail time – with more than 100 protesters imprisoned in 2022 alone.

British judges have also been delivering some of the harshest sentences for protesters in modern times. In November 2023, a 57-year-old peaceful climate protester was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for taking part in a slow march on a public road in north London for around 30 minutes.

Eight months later, in July 2024, five activists were found guilty of conspiring to cause public nuisance after participating in a Zoom call about a protest.

They received what are believed to be the “longest-ever” sentences in a case of non-violent protest in the UK in modern times, with four of the activists receiving four-year sentences, while the other was handed five years.

In July 2024, demonstrators assemble outside Southwark Crown Court in London as five Just Stop Oil activists are sentenced to the longest ever prison sentences for non-violent climate protests in the UK. Molly Robson / Global Witness

Laws limiting climate protests have also been spreading in the US, with a slew of anti-protest laws adopted in multiple states that allow harsher penalties to be imposed on activists.

More than 20 states have implemented “critical infrastructure” protection laws, aimed at those opposing fossil-fuel projects.

While powers vary, many now have the right to award penalties for trespassing and impeding operations of infrastructure such as pipelines or power plants. This has left protesters at risk of being charged with a felony – and facing many years in prison.

Similar laws are being introduced across the EU, with activists facing disproportionately harsh sentences for minor infractions, and many being subjected to draconian levels of surveillance. This includes instances of preventive detention, which includes incarcerating people before trial.

Defenders have been arrested and detained across the continent, from Finland and the Netherlands to Serbia.

Increased criminalisation, increased violence and increased censorship

Restrictive laws have limited the ability of protesters to exercise their rights to peaceful action. This can also result in increased risk and violence against defenders. The criminalisation of defenders – as offenders – can lead to increased violence from authorities and exacerbate clampdowns of marginalised groups.

In January 2023, Manuel Esteban Paez Terán – also known as Tortuguita – was shot by a police officer in the state of Georgia in the United States. The 26-year-old activist was protesting against the destruction of a local forest to make way for a police training complex.

Protestors demand justice for Manuel Paez Terán who was killed by police while peacefully protesting the controversial “Cop City” project in Atlanta, USA in January 2023. Cheney Orr / Reuters

Discrediting human rights and environmental movements

Media institutions and politicians play a major role in tainting mainstream perceptions of those protesting against climate breakdown.

In January 2024, the UN Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders under the Aarhus Convention, Michel Forst, emphasised his distress at observing the disparagement of environmental and climate defenders by the mainstream UK media and politicians.

The result, he says, is “a significant chilling effect on civil society and the exercise of fundamental freedoms.”

But the vilification of land and environmental defenders is by no means exclusive to the United Kingdom. From the Philippines to the United States, toxic narratives are being spun and damaging labels pinned on campaigners the world over, disrupting the effective functioning of civil society.

Defenders are being classified as climate extremists, and considered terrorist threats, amid increases in prosecutions, police brutality, and judicial intimidation.

Toxic narratives and laws used to criminalise work hand in hand to vilify defenders, deterring them from participating in climate action and further constraining democratic liberties – particularly views of what constitute justified protests.

In Austria, environmental activists have been pepper-sprayed by police, while in France they have been manhandled and injured by riot forces. There are reports of authorities wiretapping and tracking activists in France and Germany using legal powers normally reserved for extremist groups and organised criminals.

The authorities in Germany have been particularly aggressive, with reported raids on activists’ homes and detention to stop protests from taking place. Authorities reportedly detained at least one person for as long as 30 days without charge.

Holding climate defenders in preventive custody for more than 24 hours was used at least 80 times over an 18-month period in the German state of Bavaria.

Censorship is emerging as another tactic to restrict climate activism. In one British courtroom, activists were imprisoned just for mentioning the reason behind their direct action.

Protestors gather outside Westminster Magistrates Court in London, in 2024, following the arrest of Greta Thunberg for taking part in a peaceful protest. Carl Court / Getty

In February 2023, David Nixon, a 36-year-old care worker and climate activist, defied a judge’s order to omit any mention of climate change when addressing the jury. He had been arrested after joining a peaceful roadblock in 2021 in support of a national campaign to insulate homes and reduce emissions.

He was jailed for eight weeks for contempt of court.

In March 2024, an appeal court officially banned climate activists in England and Wales from using their beliefs and motivations as a lawful excuse for direct action protest.

In the past, use of this defence had led to acquittals, with juries in several criminal damage cases finding defendants not guilty after they argued their case.

Now, under the new ban, evidence of this kind presented by defendants, including about the facts or effects of climate crisis more broadly, would be “inadmissible”.

Strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs)

Activists across the US and the EU have been targeted by lawsuits known as SLAPPs (strategic lawsuits against public participation). These are a particularly insidious form of intimidation employed by the powerful to silence their critics, often by demonstrating financial power.

Despite geographical divides, the global struggle of defenders remains profoundly interconnected. Often defenders across the world are confronting the same familiar global corporations on their negative climate, environmental and human rights records.

Greenpeace, an environmental campaigning organisation, is facing lawsuits from the oil giant Shell in the United Kingdom that Greenpeace claims was aimed at silencing its employees for taking a stand against Shell’s activities.

Shell sought £1.7 million in damages after activists occupied an oil transportation vessel in 2023. Just a year earlier, the company reported record profits of £32.2 billion.

An Indigenous woman in Pará pauses by the river. In Brazil, Indigenous and traditional communities defending their land rights are faced with violence stemming from the expansion of agri-commodities like palm oil. Karina Iliescu / Global Witness

Indigenous Peoples have faced long-standing violence and marginalisation, meaning their vital climate knowledge is often tokenised, trivialised, or ignored. They are central to climate and nature solutions - possessing the necessary tools and knowledge - and must be and given the resources, protection, and trust to lead the way.

From invisible to indispensable: Indigenous People’s knowledge for climate action

Across the world, Indigenous Peoples have accumulated wisdom, knowledge, and practices for millennia. Rooted in deep respect for the natural world, their approaches offer powerful and often overlooked ways to achieve climate mitigation, adaptation, and resilience.

Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge can provide insights into sustainable resource management, conservation practices, and traditional adaptation strategies, all of which can help better respond to the threats posed by climate change.

And yet, far from being listened to, Indigenous Peoples have been the subject of vicious attacks. Between 2012 and 2023, 766 of them were murdered, representing 36% of all killings of environmental defenders.

At the heart of this violence is the increasing rush for land, which results in land grabbing – the acquisition of land on a large scale, often without consent, for extraction and production purposes, including agricultural commodities, biofuels, minerals and timber.

A recent declaration issued by Indigenous Peoples Rights International denounces increased criminalisation and attacks against Indigenous defenders who speak out against the impositions of mining and energy projects that violate their rights.

This dynamic has been widely reported and is well understood. As the world moves towards a greener economy, however, we risk perpetuating this model and therefore repeating the mistakes of the past.

More than half of the minerals needed for the energy transition are located in or near the lands of Indigenous Peoples and peasant peoples, who have the right to be consulted before any operations take place on their lands.

Indigenous groups protest at COP28 in Dubai 2023, where the presence of over 2,400 fossil fuel lobbyists contrasted with the attendance of approximately 350 Indigenous Peoples the same year. Jasmin Qureshi / Global Witness

To date, the meaningful participation of Indigenous Peoples in the climate negotiations space and in policy has been limited.

They continue to be represented by others – states, academics, multilateral agencies, and NGOs, replicating colonial inequities and reinforcing power dynamics that inhibit the right of Indigenous Peoples to self-determination.

In addition, they are often presented as vulnerable and homogenous global communities. Reports also often omit their unique position as holders of collective rights to lands, territories and resources.

As a result, governments’ climate solutions are inadequate because they do not account for the diversity of Indigenous Peoples or their vast differences in experiences of climate devastation.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is the UN body that analyses the escalating trajectory of the climate crisis in three principal areas: the physical science of climate change, the vulnerability of socio-economic and natural systems to climate change and options for adaptation, and strategies for mitigation.

Created in 1988, it provides governments with the latest information on the climate used to develop climate policies.

As well as influencing the climate decisions that governments and policymakers make, IPCC reports define which voices are credible. But these assessments are grounded in institutional forms of knowledge that privilege scientific socio-economic evidence over the lived and varied experiences of Indigenous Peoples globally.

And while acknowledgement of Indigenous knowledge systems has increased in official climate policy documents, alongside attendance at key climate forums (with approximately 350 Indigenous Peoples attending the COP28 climate summit in 2023), it is a far cry from the 2,456 fossil fuel lobbyists that attended the same year.

Jenifer Lasimbang and Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim are two Indigenous women from different continents and different cultures who have been actively participating in climate negotiations for years. They have shared their experience and reflections with us and pointed to possible solutions.

Jenifer Lasimbang at the International Indigenous Peoples’ Forum on Climate Change in 2022 highlights the importance of putting Indigenous Peoples front and centre in the climate space. Mike Muzurakis / IISD/ENB

Jenifer Lasimbang, Indigenous Orang Asal from Malaysia and Executive Director of Indigenous Peoples of Asia Solidarity Fund

“In Malaysia, as in many other countries, we Indigenous Peoples have been subject to wave after wave of destruction. First came the

logging and oil palm companies. As a result, nearly 80% of the land surface in Malaysian Borneo has been cleared or severely damaged.

"Now, as the world moves away from a fossil-fuel based economy, we’re seeing a rush for critical minerals, essential to succeed in the transition to a green economy.

"With Malaysia the regional leader in aluminium, iron and manganese production, extracting rare minerals isn’t new to us. But our experience so far has been that this comes at a huge environmental cost.

"The Malaysian government is issuing an increasing number of prospecting and mining licenses. We know what this new 'green rush' means for us. We know it’s going to get worse while demand for resources remains high.

"We are feeding an unsustainable and unequal global system. This will be the case as long as consumption keeps growing relentlessly.

"It is this unsustainable system that we are challenging, and not development, as we’re often accused of. The problem is that what others call development doesn’t look anything like it to us.

Trust us. Let us lead. We will take you with us

Jenifer Lasimbang, Indigenous Orang Asal from Malaysia and Executive Director of Indigenous Peoples of Asia Solidarity Fund

"Indigenous Peoples have a shared history of being ignored, attacked and silenced. We experience communities evicted from their lands, we experience our sovereignty systematically eroded, and we experience violent impunity after challenging corporate abuses.

"But we are not victims nor a problem to be solved. The opposite is true: history has proven us right. We are now seeing that it is not possible to carry on with the current level of destruction, because we are simply destroying ourselves.

"While Indigenous Peoples have been invited to participate more actively in recent years, our voices are still marginal – a 'nice-to-have' rather than an essential component. Governments need to put Indigenous Peoples front and centre in the climate space. After all, our knowledge and practices have proven effective and more sustainable.

"We want to share this knowledge with the world – as equals. But the onus should not be entirely on us. Let’s not forget that governments have the power to grant us rights over our lands and resources. Governments, too, can make sure those rights are respected. These guarantees are essential for broader climate solutions to work.

"There is only really one thing left to say: trust us. Let us lead. We will take you with us.”

Chadian activist and geographer Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim is a vocal advocate for the meaningful participation of Indigenous Peoples and the integration of their knowledge and traditions in the global fight against climate change. Brendan McDermid / Reuters

Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, Mbororo pastoralist people, Chad Coordinator of Association for Indigenous Women and Peoples of Chad and Chair of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues

“Let’s be clear: the climate crisis is already here. We’re seeing it around us – from severe droughts and raging wildfires to devastating floods and warming oceans. We are also witnessing the humanitarian cost.

"Yet we keep negotiating, as we have been doing for 30 years – even longer if we include talks at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro.

"What we now urgently need is to move from climate talks to climate action. We have all the arguments and evidence we need. What we have less and less of is time.

"I have been navigating endless challenges to get access to all those international climate negotiation spaces you now see me in. I tick all the boxes for being discriminated against: I am a woman, I am black, I am African and I am Indigenous. Ironically, my background has on occasion granted me opportunities.

"But I don’t want to be invited just so that others can say they have met their diversity criteria. I am here to be listened to because my role is ensuring that the rights of Indigenous Peoples are respected. I am here to speak for those who didn’t get the chance. And, most of all, I am here to make sure the non-Indigenous world understands.

"Indigenous Peoples have succeeded in preserving lands and natural resources in ways that the global majority has not. Political and corporate worlds look, sound, and think a certain way, with those sitting at the thresholds of power drafting laws and policies.

"Unsurprisingly, they have a very narrow worldview; they seek to preserve the systems that benefit them and see nature as something to exploit. We want to exist in harmony with it – yet it is we who are excluded from conversations about addressing our planet’s environmental crises.

Indigenous Peoples have succeeded in preserving lands and natural resources in ways that the global majority has not