New investigation reveals the alarming expansion of heavy rare earth mining in Myanmar, and the devastating cost for communities and the environment

China has long dominated the world's supply of heavy rare earths, minerals needed to build electric vehicles and wind turbines. Demand for these products is skyrocketing as we rush to meet climate goals, but there is a problem at the root of the supply chain.

The processes used to extract heavy rare earths are highly polluting, ravaging landscapes and poisoning waterways. As concerns over the environmental toll of extraction have grown in China over the past decade, more and more domestic mines have been shut down. Yet global demand is growing rapidly, and China remains the world's largest processor.

But with many of its own mines now closed, where is China's supply of these minerals coming from?

A six-month investigation by Global Witness followed the outsourcing of this highly toxic industry across the Chinese border into Myanmar.

There, heavy rare earth mining has exploded so quickly that within just a few years a mountainous corner of Myanmar, known as Kachin Special Region 1, has become the world's largest source of supply. This region is a semi-autonomous territory run by militias that are affiliated to Myanmar's brutal military regime. The mining is illegal under Myanmar's laws, and hardly exists on paper.

Yet the damage that global demand for products manufactured by international companies is fuelling in this remote, lawless part of the world is all too real for the communities who are now risking their lives to defend their land.

For Zau*, a local worker, the mining boom is a rare chance to make money. He is paid 3,800 yuan ($600) in cash every month, around twice the average salary in Myanmar.

He works in the shadows, at a mine near the Chinese border, for a company that has no permits. On paper, Sin Kyaing Company is owned by a local militia leader called Lagwi Bawm Lang. But like other Burmese companies in the rare earth mining industry, it is really a front for illegal investment by Chinese businesspeople.

Zau's job is to remove vegetation and drill holes into the mountains. Then ammonium sulphate solution is injected into the holes, effectively liquefying the earth. Once the chemicals have percolated through the mountainside, the solution is drained into bright blue collection pools, where minerals are precipitated out in a process called in-situ leaching.

After this mountain has been leached, Zau and his colleagues will abandon the contaminated site, moving to the next place and starting all over again.

“In my opinion, the mountains will definitely collapse one day,” Zau told Global Witness, alluding to the risk of landslides.

Despite being paid well, he is worried about the harm the chemicals are causing to the water supply, and therefore to the health of local people.

“People from the surrounding villages are facing difficulties getting drinking water,” he said. “Even healthy people like us feel dizzy if we inhale these odours for a long time.”

The mountains beneath Zau's feet are rich in ores of dysprosium and terbium, the two most valuable of the heavy rare earth metals. Described by an industry expert as “basically irreplaceable”, we rely on them for a whole range of clean energy and smart tech products – from the smartphone you may be using to read this story, to your energy-conserving home electronics.

But their most important use, representing 90% of their value, is in permanent magnets, which are needed to make motors and generators for electric vehicles and wind turbines.

The stakes are high: it would be almost impossible to build a low-carbon future without these products, and many of them currently do not work well without heavy rare earths.

A few years ago, there were just a handful of mines in this remote area of north-eastern Myanmar bordering China

Now, they sprawl across an area the size of Singapore

In March 2022, Global Witness commissioned the remote sensing company Planet to fly a satellite over the region

We found over 2,700 mining collection pools at almost 300 separate locations

The environmental challenges that come with this type of mining in China have spread to a neighbouring nation

— Ryan Castilloux, Adamas Intelligence

China has controlled the global rare earth sector since the 1980s. But as its domestic mining industry boomed, the cracks began to show – illegal mining was rampant, the environment was suffering, and there were concerns over dwindling resources, particularly of heavy rare earths. From 2016 the central government intensified efforts to clean up the industry and closed many of the heavy rare earth mines in Ganzhou, Jiangxi Province, known as China's “rare earth kingdom”.

A government sign in China's Jiangxi Province exhorting the sustainable development of the rare earth industry in 2010. Credit: Adam Dean/Panos Pictures

This meant that China's state-owned processers needed new sources of raw materials to continue supplying the global market. They turned to neighbouring Myanmar, where there are rich deposits similar to those in Jiangxi.

Thousands of people crossed the porous border to set up and work in the new mines, with one report by commodity research firm Roskill estimating that between 2016 and 2019 as many as 16,000 people moved from Ganzhou to Myanmar to mine rare earths.

An electrician from China's Jiangxi Province (left) and his work permit (right) are pictured in the rare earth mining area in Myanmar's Kachin State.

Workers operate Chinese-made machinery at a rare earth mine in Myanmar's Kachin State

There are reports that the setting up of these operations within Myanmar was funded to a degree by certain Chinese state-involved entities ... It's probable they had a subsidiary go over, develop these routes, set up an independent company and operate through that.

— Rare earth supply chain expert

Chinese workers make up almost half of the 30 to 100 employees at each mine, according to a 2018 survey of residents, seen by Global Witness. Multiple sources told Global Witness that Chinese workers hold the skilled roles, while Burmese workers, including children, do most of the manual labour.

The mining method used is the same as in Jiangxi and the mines are still supplying the same Chinese state-owned companies that control 80% of global rare earth refining.

As commodity research firm Roskill wrote in a September 2021 report: “All Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs), except for those [that] focus on light rare earths, have become reliant on Myanmar sources over the past four years, and now face supply chain risks with few alternative suppliers.”

But instead of applying for permission to mine from Myanmar's central government, businesspeople have negotiated backroom deals with the militias that control Kachin Special Region 1.

The region is run as a fiefdom by an ageing warlord called Zakhung Ting Ying, who controls militia units that are part of the Myanmar military's chain of command, and others that are loyal to the military, including the militia led by Zau's boss.

There is a high risk that revenues from rare earth mining are being used to fund the military's abuses against civilians, which have intensified since its February 2021 coup. This is nothing new; Myanmar's military has funded itself for decades by looting the country's rich natural resources, including the multi-billion-dollar jade, gemstone, and timber industries.

Recognising that the industry finances the regime, Myanmar's democratically elected government-in-exile has declared all rare earth mining operations illegal.

For the past five years, vast amounts of cash from the rare earth trade have flooded Zakhung Ting Ying's territory. Along with members of his family and other militia leaders, he has become the industry's central broker. Together, they control a network of Myanmar-registered companies, including the company where Zau works. These entities are registered as domestic businesses, but act as fronts for illegal Chinese investment and take a cut of the profits.

China imported over $200M of rare earths from Myanmar in December 2021

Foreign investment in small- and medium-scale mineral production is illegal under Myanmar law. Companies can apply for an exemption from the central government, but none have been issued. Despite this, Zakhung Ting Ying's militias grant permission for companies to mine on land that they have often confiscated from local people, and bypass immigration rules to issue unofficial permits to Chinese mine workers.

In the words of one Chinese mine worker: “In China, you can never buy the law with money ... but in Myanmar, we can buy the law with money. We can do anything with money.”

The militias issue local miners with ID cards that enable them to work at the mines, and they collect bribes for access to the mining sites at checkpoints on the roads. They also control border trade, illegally taxing exports of rare earths to China.

In Jiangxi, where many mining operations remain closed, Chinese officials have estimated that the clean-up bill for the industry's environmental damage will total 38 billion yuan (around US$5.6 billion), with a full recovery expected to take as long as 100 years.

Discarded pipes from rare earth mining operations line the banks of Zuk Lang stream

In Myanmar, where the industry is illicit and controlled by armed groups, and it is dangerous for civil society groups to operate, nobody has quantified the environmental cost – and it would be impossible to do so, given how quickly the mines are expanding.

Our investigation reveals that the impacts of mining on local ecosystems, livelihoods and access to safe drinking water have been devastating. Zau's concern that the mountains may collapse is justified – in China's Ganzhou more than 100 landslides have been reported. In Myanmar, deforestation has also led to soil erosion and chemical pollution has harmed ecosystems.

Residents are also worried about hazardous waste from the mining area flowing directly into the N'Mai Kha River, a tributary of the Ayeyarwady, Myanmar's most important river, whose basin is home to two-thirds of the country's population of 54 million people.

Just as in China, where Jiangxi Province is the source of two rivers that are important drinking water sources for millions of Chinese living as far downstream as Hong Kong, there are fears that the contamination could spread.

Multiple health issues have have been reported near the rare earth mines in China because of in-situ leaching, including osteoporosis, respiratory diseases, and gastrointestinal, skin and eye problems.

We are worried that everyone is in danger

— Community elder

People living near the mines in Myanmar have already begun to experience these symptoms, according to the 2018 survey of residents. “When the villagers cross the river, their legs begin to itch; if they have a wound, it becomes worse,” the survey found.

Residents told the survey that they no longer fished, swam, or washed in the local rivers, and that animals, including their livestock, had been poisoned by the toxic water.

This is particularly concerning because the mountains are richly biodiverse and are home to dozens of rare and endangered plant and animal species, including red pandas and gibbons.

“Now there are no birds or animals in the forests,” a community representative told Global Witness, in comments echoed by multiple other residents. “There are no more fish in the rivers,” said another. “The wild animals are gone.”

Crops grown near the mines are contaminated too, residents said, and the Chinese traders who previously bought black cardamoms, quinces, oranges and walnuts now refuse to buy local products.

“Both the land and the people are ruined,” a community leader told us. “Local people who have been here since their ancestors' time have become strangers in their own land.”

Many people are afraid of speaking out against the mining because they fear retribution. “No one wants to give up their ancestors' lands, but if they [resist] they can be killed,” explained a Kachin civil society representative.

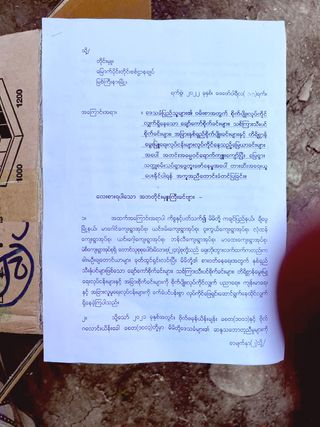

Despite the risks, in February this year a group of community leaders wrote to the military's Northern Command, asking the commander to intervene and stop the expansion of mining into their villages. They made the complaint after two leaders of a local militia unit called village representatives into a meeting and threatened to shoot them if they refused to give up their land.

Protest letter from villagers to Myanmar's military

You, village leaders, should solve this issue. Otherwise, I will have to start shooting and killing people from now on. Do not underestimate me. I am not a child. This is not child's play.

— Galaw Ying Hkaw at a recent meeting

We spoke to the community leaders who wrote the letter, and they told us they would continue to speak out despite the threats because if the new mines are built, they risk losing everything.

“Everyone will be in trouble and danger if the rare earth companies come in,” said one.

Another added: “We have seen what happened in other places .... If it happens to us, we will not be able to sell what we grow. It would be no different from killing us.”

The disturbing reality is that the cash that fuels these abuses ultimately stems from the global push to scale up renewables.

The odds are stacked against the villagers who speak out against mining in Kachin Special Region 1, because with total demand for processed rare earth minerals for magnet production set to triple by 2035, Zakhung Ting Ying and his militias have unprecedented backing for their brutal rule – the global transition to clean energy currently depends on rare earth mining in Myanmar.

A truck delivers ammonium sulphate to a rare earth mine

Bags of rare earth are piled up at a mine to be processed before being exported to China

All the heavy rare earths mined in Myanmar are exported to China. There, the industry is controlled by five state-owned companies that have a monopoly on mining and processing (as well as a sixth company that mines only light rare earths) and which have been merged or are set to be acquired over the next few years to form a single group. Among them, the biggest player is China Southern Rare Earth Group with over 40% of the officially sanctioned mining quota.

However, it is not clear how much mining the company is doing. China does not publish production figures, while research by a Chinese customs official states that China Southern imports 70% of its raw materials from Myanmar and gets the other 30% from recycling.

A 2021 post on China Southern's website says that its parent company Ganzhou Rare Earth Group “has taken the lead in opening up the path of importing rare earth resources from Southeast Asian countries such as Myanmar”, and “has seized more than 50% of overseas rare earth resources” and “imported 10,000 tons of ... rare earth raw ore” after Ganzhou's rare earth mines were closed over environmental concerns.

While there is very little public information linking China's state-owned companies to Myanmar's illegal mines, we uncovered a range of evidence indicating that at least two of the other four heavy rare earth processing giants – China Minmetals Rare Earth Company and Guangdong Rare Earth Group – are sourcing from Myanmar.

Imports from Myanmar now exceed China's domestic mining quotas, so even if the mines in China were producing at full capacity, Myanmar would remain the country's single largest source of rare earths – and with no other companies in China legally allowed to process this material, there is nowhere else for imports to go.

Imports from Myanmar surpassed China's quota for heavy rare earth mining in 2021

This leaves not only Chinese processors but the entire global permanent magnet industry highly vulnerable to supply chain shocks.

Myanmar has become such an important supplier that it would be very tough to increase quotas sufficiently to fill that gap.

— Ryan Castilloux, rare earth industry expert

Once they are processed by China's state-owned companies, Myanmar's rare earths pass down the supply chain to permanent magnet manufacturers. One of the largest is JL Mag Rare-Earth Company, which sources some of its heavy rare earths through a long-term supply agreement with China Southern. JL Mag is a key supplier of permanent magnets to some of the world's best-known manufacturers of electric vehicles, wind turbines and electronics.

We wrote to all the companies and individuals named in this investigation to give them an opportunity to comment on the record, and three of them replied.

Siemens Gamesa said it recognised that rare earth mining comes with “significant environmental and social risks” that the company is trying to mitigate, including by phasing out heavy rare earths from its products. It said initial feedback from its suppliers indicated they only sourced from China.

Nidec Corporation and Robert Bosch GmbH, which both buy permanent magnets containing dysprosium and terbium from JL Mag, said that they only source products containing recycled rare earth. Nidec said that China Southern supplies 100% recycled rare earth products to JL Mag, and that it believed the magnets being used for its products were unrelated to mining in Myanmar, but that it would look further into the matter. JL Mag did not respond to our request for comment.

Even if companies are buying recycled rare earth products, there is a risk these products will be “contaminated” with heavy rare earth from Myanmar because materials from various sources get mixed together during processing, a rare earth industry expert told Global Witness.

“If you're buying magnets, particularly the high-grade magnets more reliant on heavy rare earths, there's a good chance some amount of material has come from Myanmar” he said.

People walk past a Tesla dealership in Shanghai, China. Credit: Qilai Shen/Panos Pictures

If unregulated mining in Myanmar continues, our rush to embrace a greener future will be devastating for the communities in Kachin Special Region 1 who are now risking their lives to defend their land against the fast-expanding industry.

“We have been living here for five hundred years,” a local resident who is trying to stop the expansion of rare earth mining into his village told us. “If rare earth mining comes to this area, there will be no future for our people. Everything will disappear.”

Read our recommendations to companies and governments here.

Sign up for emailsSign up for emails from Global Witness

We began this investigation in December 2021 after receiving reports of widespread illegal rare earth mining in Kachin Special Region 1. Looking at satellite imagery, we detected a rash of cyanic pools emerging across the region. We used historical Sentinel-2 imagery to assess the rate of change and the spatial extent of the affected area, before tasking a Planet satellite to retrieve a high-resolution image in March 2022. All mining sites in the resulting image were identified through manual inspection. Explore them here.

At the same time, we gathered information during a field trip to the rare earth mines and through interviews and correspondence with more than 50 sources including mine workers, public officials, representatives of civil society organisations, journalists, and community leaders in Kachin State. We also interviewed industry experts, academics and other stakeholders including companies that use rare earths in their products. Given the heightened risk of violence since the military coup in Myanmar we do not reveal the identities of most of the sources we quote in this report.

Many of the people we interviewed also shared documentary evidence with us, including photographs and videos of mining operations, an unpublished 2018 survey by local civil society groups about the social and environmental impacts of rare earth mining, a 2019 report on illegal rare earth mining by an inspection team sent to the mining area by the civilian government, and protest letters sent to the government and the military by residents, calling for rare earth mining to stop.

This investigation also draws on a desktop review of publicly available English, Burmese and Chinese-language sources including posts on social media, media articles, industry analyst and civil society organisation reports, customs records, maps, academic papers, Myanmar Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative reports, company websites, annual reports and investor presentations, corporate records held with Myanmar's Directorate of Investment and Company Administration, laws, and related notifications.

*Zau is not his real name

Unless otherwise stated all images are credited to Global Witness